Working on microcontrollers is a far cry from the essentially unlimited memory and floating point operations available in Python and other high level languages. Here’s what I have been learning at my first internship…

Restricted Memory

While working there, I was assigned to a project that required usage of a Texas Instruments MSP430 microcontroller.

While there were many quirks with working on MCUs like this (like having to ditch JetBrains & VSCode altogether!), the

biggest quirk isn’t working with C: it’s working without malloc altogether.

On low memory devices like this, memory is extremely limited and there is no certainty that your code will not leak memory.

Usage of malloc and other dynamic memory allocation methods are considered innately dangerous - while there is a chance

you will write perfect code that will properly allocate/deallocate, you can’t be certain that your complex program

won’t run out of memory on such a small footprint to work with.

Instead, variables are assigned either inside methods for short periods (and passed around), or they are assigned statically and globally. It appears that the libraries I use personally prefer globally accessible variables, which 99% of the time, is very wrong - but in Microcontroller land, global variables are your friend.

#include <stdint.h>

uint8_t uid[4]; // A unique identifier

int main(void) {

UID_generate(uid, 4); // Pass the pointer, the function writes to it (and does not return it)

UART_putUid(uid, 4); // Write the UID to UART

}void UID_generate(uint8_t uid, int length) {

uint8_t i = 0;

while(i < length)

uid[i++] = RANDOM_char();

}

void UART_putUid(uint8_t* uid, int length) {

uint8_t i = 0;

while(i < length)

UART_putChar(uid[i++]);

}

void UART_putChar(uint8_t value) {

while(!(UCB0IFG & 0x1));

UCB0TXBUF = value;

}There’s not much more to this - don’t use malloc, stick to the stack for actively executing methods and use global variables

when you need to go into low power mode while maintaining state.

Overall, this doesn’t hinder ones ability to write working code - the features are still there, but the way you access methods, store data & manipulate is re-organized - sometimes at the detriment to quality & refactoring efforts.

Data Framing Tricks

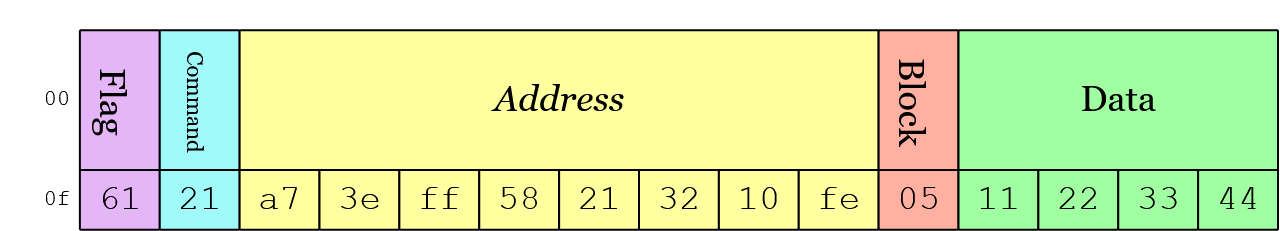

While at my internship, I used my MSP430 microcontroller to communicate with various devices over UART and SPI. I also sent commands to a ISO15693 NFC wafers. All of these interfaces are extremely low level and the best documentation I have is often just a PDF and some random code scattered across the internet. There is no library to speak of, usually.

Communicating at a low level like this requires reading and writing individual bytes of data into frames, or arrays of bytes with a well-defined structure.

Traditionally, commands are built statically all at once in a mostly hardcoded manner:

uint8_t offset = 0;

ui8TRFBuffer[offset++] = 0x61;

ui8TRFBuffer[offset++] = 0x21;

ui8TRFBuffer[offset++] = 0xA7;

ui8TRFBuffer[offset++] = 0x3E;

ui8TRFBuffer[offset++] = 0xFF;

ui8TRFBuffer[offset++] = 0x58;

// ... You get the ideaInstead, what if we could format this into a struct that we could pass around on the stack with a pointer?

struct AddressedSingleBlockWrite {

uint8_t Flag;

uint8_t Command;

uint8_t Address[8];

uint8_t Block;

uint8_t Data[4];

};

int main() {

struct AddressedSingleBlockWrite command;

command.Flag = 0x20 | 0x40;

command.Command = 0x21;

uint8_t address[8] = {0xA7, 0x3E, 0xFF, 0x58, 0x21, 0x32, 0x10, 0xFE};

memcpy(&command.Address, &address, sizeof(command.Address));

command.Block = 0x05;

uint8_t data[4] = {0x11, 0x22, 0x33, 0x44};

memcpy(&command.Data, &data, sizeof(command.Data));

}Now we have a defined structure in our source code and we can move and manipulate various parts of our command structures without having to deal with hardcoded offsets. Still though, if we want to copy this command structure into the buffer, we have to individually copy each part of the command - which will break the second we modify its structure.

There’s a fantastic solution for it: Unions.

union ASBWUnion {

uint8_t data[15];

struct AddressedSingleBlockWrite marshalled;

};union ASBWUnion demarshalled;

demarshalled.marshalled = command;

for (int i = 0; i < 15; i++)

printf("%x ", demarshalled.data[i]);60 21 a7 3e ff 58 21 32 10 fe 5 11 22 33 44unions are special datatypes that share a single memory footprint (equal to it’s largest member) starting at the exact same point memory.

They combine neatly with structs to allow us to represent the AddressedSingleBlockWrite as a single byte array.

Reversing Endianness

If you check out TI’s sloa141 PDF on ISO 15693 commands, you’ll notice that many of the examples have sections of their bytes reversed - sections like the Address and Data sections, but not the entire compiled command.

One such example, 60 21 9080C2E5D2C407E0 06 55443322, has the Flag, Command,

Address, Block and Data in that order.

But for this particular example, how could the address be E007C4D2E5C28090?

How could the data be 22334455? This odd ordering has a name - Endianness - the order of bytes as the underlying architecture understands it.

While for my particular usage, reversing endianness was not needed, it’s an interesting problem that can be solved quite easily with our new data structure.

void ReverseEndianness(struct AddressedSingleBlockWrite asbw) {

uint8_t temp;

int i = 0;

for (; i < 4; i++) {

temp = command.Address[i];

command.Address[i] = command.Address[8 - i - 1];

command.Address[8 - i - 1] = temp;

}

for (i = 0; i < 2; i++) {

uint8_t temp = command.Data[4 - i - 1];

command.Data[4 - i - 1] = command.Data[i];

command.Data[i] = temp;

}

}Conclusion

Working in a restricted memory space is not that hard once you get used to the lack of normal functions such as malloc

and printf, but balancing performance, power consumption, memory allocation and code quality gets harder the more

complex your program gets.